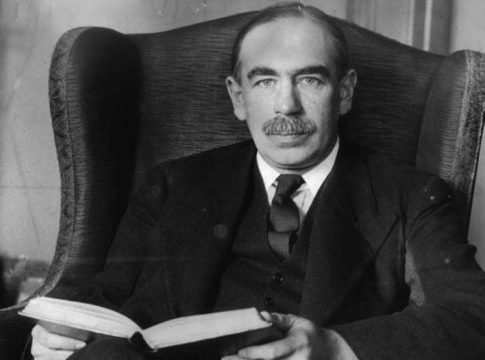

A recent article by Daniel Lacalle titled “How Keynesians Got The US Economy Wrong Again” highlights a growing disconnect between John Maynard Keynes’ economic theories and the real-world outcomes. Despite the confident predictions from leading Keynesian economists, the U.S. economy in 2025 is proving more resilient than anticipated. The Federal Reserve’s tightening measures have not led to the predicted “hard landing,” and growth continues to defy expectations. While inflation remains somewhat persistent, it is gradually declining, and the economy does not adhere to the neat, linear paths suggested by traditional models.

This latest setback for Keynesian orthodoxy is part of a broader narrative. The failures are not isolated incidents but rather the expected consequences of a flawed framework that policymakers have relied on for decades. Keynesian economics has not only missed the mark in 2025 but has consistently failed to meet its promises for over forty years, and the repercussions are becoming increasingly apparent.

At its essence, Keynesian economics is deceptively straightforward: when private sector demand falters, the government should borrow and spend to fill the gap. The theory posits that temporary fiscal stimulus will smooth out business cycles, lower unemployment, and quickly restore the economy to full capacity.

The crucial term here is “temporary.” Keynes emphasized that governments should run deficits during downturns and surpluses during expansions, with the expectation that debt incurred to stimulate the economy would be repaid once conditions improved.

In practice, however, this fiscal discipline has not materialized. Politicians found that voters favored stimulus but opposed austerity. Since the 1970s, deficits have become a permanent fixture of U.S. fiscal policy, irrespective of the business cycle. The consequences are sobering: the national debt has surpassed 120% of GDP, entitlement programs are structurally underfunded, and each crisis necessitates larger interventions that yield diminishing returns.

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a massive Keynesian experiment. From 2020 to 2022, the federal government injected over $5 trillion into the economy, with the Federal Reserve slashing interest rates to near zero and expanding its balance sheet by $120 billion monthly. According to Keynesian principles, this unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus should have sparked a lasting economic boom.

The Limits of Artificial Growth

However, as previously noted, the flood of stimulus only temporarily boosted economic growth by bringing future demand into the present, creating several challenges.

One major issue was the surge in demand on a supply-constrained economy. With the economy effectively “shut down” due to government restrictions, stimulus payments led to increased demand. Basic economic principles dictate that as demand rises, prices will too, resulting in significant inflation. During the pandemic, inflation, excluding housing and healthcare, soared to nearly 12%. Today, as the economy slows and stimulus fades, that rate has dropped to just 1.61%.

Moreover, the so-called “economic boom” fueled by demand-pull stimulus is fading as the economy gradually returns to a debt-to-output ratio of approximately $3.50 for every dollar of economic activity. Following the pandemic lockdown, nominal growth peaked at an unprecedented 17.5%. However, this surge in demand contributed to a spike in inflation, which reached 40-year highs, surpassing 9% in 2022. While inflation is now declining towards the Federal Reserve’s 2% target, it remains stubbornly persistent.

Monetary Policy’s Broken Mechanism

A significant flaw in modern Keynesian policy is its heavy reliance on central banks. Through interest rate cuts and quantitative easing (QE), monetary stimulus has become the default response to any economic slowdown. Yet the link between monetary policy and real economic activity has fundamentally broken down. Artificial interventions and modern monetary theory (MMT) have proven ineffective because the underlying mechanisms have failed.

“The promise of something for nothing will always be appealing. Thus, MMT should be viewed more as political propaganda than a genuine economic strategy. Like all propaganda, it must be countered with real facts,” notes an economic analyst. Meanwhile, the velocity of money, or the rate at which money circulates in the economy, while recovering somewhat, is on a downward trend. This means that while the Fed can inject liquidity, it fails to circulate in a productive manner, casting doubt on future GDP growth.

With weakening economic growth and declining inflation—indicators of faltering consumer demand—banks have little motivation to expand lending in a climate of tighter regulations and poor credit quality.

Another critical issue is that Keynesian models assume a straightforward cause-and-effect relationship between government spending and economic output, focusing mainly on aggregate demand while neglecting key dynamics like debt saturation and supply chain vulnerabilities.

In today’s highly financialized economy, government spending does not circulate effectively. Much of it gets trapped in financial markets, inflating asset prices rather than fostering productive investment. Ultra-low interest rates, a hallmark of Keynesian policy, discourage savings and promote debt-fueled speculation, leading to misallocation of capital and malinvestments in unproductive assets.

The Warnings of Hayek

The Austrian school of economics, particularly Friedrich Hayek, offers a stark contrast to Keynesian thought. Austrian economists argue that prolonged periods of low interest rates and excess credit creation create dangerous imbalances between saving and investment. Low interest rates encourage borrowing, which leads to an expansion of credit and money supply.

As this credit-fueled boom becomes unsustainable, it results in widespread malinvestments. When the exponential growth of credit can no longer continue, a contraction occurs, shrinking the money supply and reallocating resources more efficiently.

Modern policymakers resist allowing this natural correction. Each economic downturn prompts more aggressive stimulus, delaying necessary adjustments and leading to persistent economic imbalances. Inefficient businesses survive on cheap debt, zombie firms multiply, and innovation suffers. Each economic expansion is weaker than the last, requiring larger interventions to stay afloat.

Perhaps the biggest misconception perpetuated by Keynesian economists is that debt-financed stimulus is a free lunch. In reality, servicing this debt creates a significant economic burden. The Congressional Budget Office predicts that U.S. interest payments will soon surpass national defense spending, reaching $1.5 trillion annually by 2030, assuming current rates remain stable.

This isn’t just a fiscal problem; it’s a macroeconomic drag. Funds allocated for interest payments divert resources from infrastructure, education, and productive investment. Rising debt levels crowd out private investment, distort capital markets, and limit flexibility in responding to future crises.

In Conclusion: The Failings of Keynesian Theory

For the past 40 years, successive administrations and the Federal Reserve have adhered to Keynesian monetary and fiscal policies, believing in their effectiveness. However, the reality is that much of the economy’s growth has been driven by deficit spending, credit expansion, and diminished savings.

This has curtailed productive investment and slowed overall economic output. As economic growth falters and wages stagnate, consumers have taken on more debt, reducing savings. The increased leverage necessitates higher incomes to service debt, which in turn hampers consumption.

Moreover, many government spending programs redistribute income from workers to the unemployed. While Keynesian economists argue that this enhances the welfare of those affected by recessions, they overlook the reduced productivity that results from shifting resources away from investment.

These issues have collectively weighed on the economy’s overall prosperity. Most striking is the current economists’ failure to recognize the futility of trying to “solve a debt problem with more debt.”

This is why Keynesian policies have faltered—from “cash for clunkers” to “quantitative easing.” Each intervention either pulls future consumption forward or stimulates asset markets, leaving a “void” that needs continual filling. Creating an artificial wealth effect diminishes savings that could otherwise be directed toward productive investment.

It’s time to acknowledge that we are on a perilous path.