Scott Sumner

I recently spoke to some Bentley University students (via zoom) about my views on the Great Recession. In this post, I summarize the substance of my talk. Long-time readers will have seen these arguments, but this blog has attracted some new readers who have asked me to justify contrarian claims such as, ”Tight money caused the Great Recession.” Here (in bold print) are 18 common misconceptions about the Great Recession:

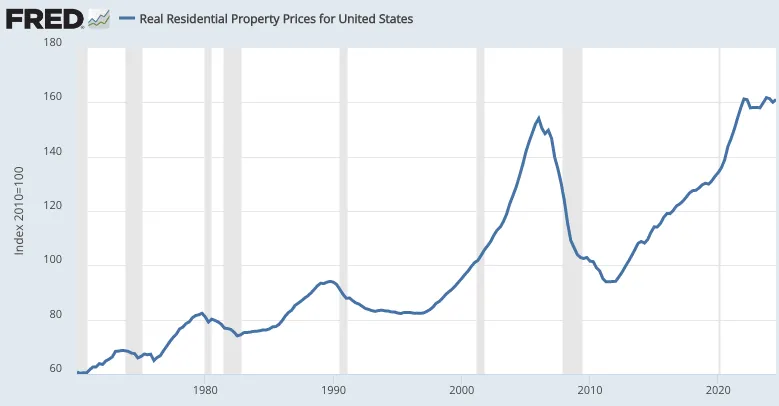

- There was a housing bubble that peaked in early 2006. The term ‘bubble’ often refers to excessive rates of new home building and/or irrationally inflated home prices. The US was not building too many homes in 2005-06; if we were you’d expect falling house prices, not rising prices. Indeed the inadequate level of home building during recent decades (due to the excesses of Nimbyism) is arguably the biggest economic problem in America. It is one of the most important reasons that living standards for the middle class have been rising more slowly than during the mid-20th century. In addition, there is no evidence that housing prices were irrationally high during the 2005-06 boom. If high housing prices caused the Great Recession, why didn’t the equally high (real) housing prices of 2022 cause a recession? The high housing prices of recent years are fully justified by the “fundamentals”.

- The big drop in housing construction played a major role in the 2008 recession. This is factually inaccurate. The vast majority of the decline in home building occurred between January 2006 and April 2008, when residential construction declined by more than 50%. During that period of time, the unemployment rate barely budged, edging up from 4.7% to 5.0%. In a well functioning economy with adequate NGDP growth, a sharp decline on one sector, even a big sector, does not cause a recession. Other parts of the US economy continued to boom throughout 2006 and 2007. Unemployment only rose sharply after the spring of 2008, when tight money sharply reduced NGDP growth, leading to employment declines across a wide range of sectors.

- The subprime mortgage fiasco largely explains the banking crisis. Most of the bank failures during the Great Recession occurred because of defaults on commercial loans, not subprime mortgages. This is exactly what you’d expect to occur when there is an unusually dramatic decline in NGDP growth. The banking crisis is not a puzzle that needs to be explained; the puzzle would be if an 8% drop in NGDP growth rates did not cause a banking crisis.

- The banking crisis caused the Great Recession. The post-Lehman banking crisis occurred 9 months after the recession began, just as the banking crises of the 1930s occurred well after the Great Depression began. Again, banking crises are a symptom of falling NGDP, not a cause. Think of nominal GDP as the income that people and business have available to repay nominal debt.

- A rapid economy recovery is not possible after a financial crisis. The fastest growth in industrial production in US history occurred in the spring and summer of 1933, despite much of the banking system being shut down. That’s because dollar devaluation led to rapid growth in NGDP. Monetary policy drives NGDP, and NGDP drives the business cycle in highly diversified economies like the US.

- After the debt crisis, it was appropriate for aggregate demand to decline. Americans needed to “tighten their belts.” This conflates aggregate demand with consumption. When you’ve gone too far in debt, it makes sense to work harder, not take a long vacation. For a country, the response to too much debt should be more employment, more work effort, more production, not less. That’s how you “sacrifice”.

- The Fed adopted an easy money policy in 2008. This is a textbook example of reasoning from a price change. Nominal interest rates did decline in 2008, but the natural interest rate declined even more rapidly. Other than short-term nominal interest rates, every other financial market indicator suggested that money got tighter over the course of 2008. Interest rates are not a good policy indicator.

- Perhaps nominal rates are misleading, but surely the real interest rate is a good indicator of monetary policy. No, for the same reason that nominal rates are unreliable. Real interest rates also move around for a wide variety of reasons, not just monetary policy. In any case, real interest rates rose sharply throughout September, October, and November 2008, so if you believe real rates are the correct policy indicator, then you should agree with my claim that a tight money policy caused the Great Recession.

- The Fed certainly did not cause the Great Recession, at most they did too little to avert it. The recession was triggered by falling velocity, not slower money growth. This is factually inaccurate. At the point where the economy first tipped into recession (December 2007), growth in the monetary base was slowing sharply, whereas base velocity was increasing. Between August 2007 and May 2008, the monetary base increased by only 0.2%, far below the previous trend of roughly 5%/year. Velocity actually increased over that 9-month period. To be clear, the base is not a reliable indicator of the stance of monetary policy (as it rose sharply in late 2008.) But the problem in late 2007 and early 2008 was more than simply errors of omission by the Fed. It was tight money.

- The Fed did all it could to boost the economy in 2008; it simply ran out of ammunition. There are two problems with this claim. The Fed didn’t even cut its target interest rate to a level close to zero (actually 0.25%) until mid-December 2008, by which time most of the decline in NGDP had already occurred. In addition, the Fed has many tools that it can use after interest rates hit zero. Fiat money central banks never “run out of ammunition.”

- The Fed did not intend its new program of interest on bank reserves to have a contractionary effect on the economy. Yes, it did. As Susan Woodward and Robert Hallpointed out, the Fed’s own explanation for the policy “amounts to a confession of the contractionary effect.” The Fed indicated that they implemented the policy to prevent interest rates from falling. The policy was enacted a few weeks after Lehman failed, when the global economy was plunging into a deep slump. An unforced error.

- The zero lower bound problem held back the recovery during the early 2010s. When interest rates rose above the zero lower bound in late 2015, the economic recovery did not accelerate. This suggests that the sluggish growth in NGDP during the early 2010s was not caused by interest rates being stuck at zero.

- Blaming the recession on falling NGDP is almost a tautology. If that were true, then poor countries could produce prosperity simply by printing lots of money, which would boost inflation, and thus NGDP growth. Does that seem likely to work? It’s true that in the US (but not Zimbabwe) there is a positive correlation between NGDP and real GDP, just as there is often a positive correlation between NGDP and other variables such as the money supply and interest rates. But any theory that NGDP causes changes in RGDP requires a plausible causal mechanism. In my view, that mechanism is sticky nominal wages.

- The US caused the Great Recession, and Europe was hit by the ripple effects of the US crisis. The recession began at the same time in the Eurozone, and from the very beginning it was at least as bad in Europe. That’s because the hawkish ECB’s monetary policy was even more contractionary than Fed policy. If it were true that the US housing/banking crisis caused the recession, then it would have been much worse in the US.

- The Eurozone debt crisis explains why Europe’s recession ended up being much worse than the US recession during the 2010s. Again, this confuses cause and effect. The ECB sharply tightened monetary policy in 2011, causing a double dip recession. That’s what triggered the eurozone debt crises (although irresponsible fiscal policies in places like Greece also played a role.)

- The US policy of fiscal austerity slowed the recovery in 2013. This is what Keynesian economists like Paul Krugman predicted, indeed he suggested that 2013 would be a sort of test of the market monetary model. If so, we passed with flying colors, as GDP growth sped up after fiscal austerity began in January 2013. The Fed anticipated the fiscal tightening, and offset the effects with a more expansionary policy of monetary stimulus. Conversely, the tax rebates of the spring of 2008 failed to boost spendingbecause the Fed offset them with tighter money.

- High unemployment in the US during the 2010s was mostly due to “structural problems”. Contrary to the claims of many on the right, most of the unemployment was due to a shortfall in aggregate demand, and the unemployment rate fell back to a low level once wages fully adjusted. Don’t be a supply-sider or a demand-sider, be a supply and demand-sider.

- More generous unemployment benefits led to increased aggregate demand, and this helped to boost employment. Contrary to the claims of many on the left, higher unemployment benefits do discourage work and lead to less employment. Don’t be a supply-sider or a demand-sider, be a supply and demand-sider. Keynesians predicted that employment growth would not accelerate after the extended unemployment benefit program lapsed in early 2014. They were wrong—employment growth did strongly accelerate in 2014.

In a recent post, I suggested that when people say, “The consensus view is X, but Y is actually true”, they intend their comment as a sort of prediction of future belief, a claim that, “Eventually, society will come to see Y as being true.” Think of this post as a prediction of the future consensus view. For instance, in late 2008 I complained that monetary policy was too tight. In his 2015 memoir, Ben Bernanke acknowledged that the Fed had erred in not cutting interest rates during the Fed meeting immediately after Lehman failed in September 2008.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of economists still believe most of these myths.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Censational Market.